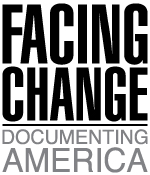

First National Bank and Trust Building, built 1925.

First National Bank and Trust Building, built 1925.

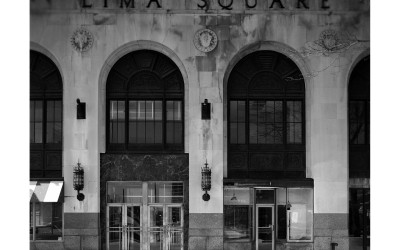

Ohio Foam Novelties factory, at 435 N Elizabeth Street.

Ohio Foam Novelties factory, at 435 N Elizabeth Street.

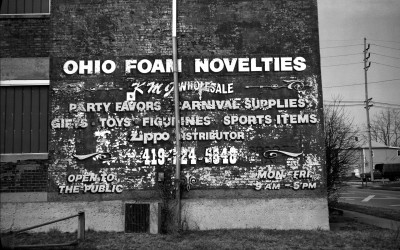

Downtown Lima resembles many Midwestern small towns with many closed businesses and boarded up storefronts, even as some new buildings and industry continue.

Downtown Lima resembles many Midwestern small towns with many closed businesses and boarded up storefronts, even as some new buildings and industry continue.

Kewpee fast food restaurant, built 1928 and in continuous operation. Approved for the National Registry of Historic Places but not listed due to the owner’s objections. Kewpee is a small franchise chain with its headquarters in Lima and five remaining locations in Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Kewpee fast food restaurant, built 1928 and in continuous operation. Approved for the National Registry of Historic Places but not listed due to the owner’s objections. Kewpee is a small franchise chain with its headquarters in Lima and five remaining locations in Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Historic 1884 courthouse demolished after preservationists failed to save it, in the nearby town of Tiffin, Ohio.

Historic 1884 courthouse demolished after preservationists failed to save it, in the nearby town of Tiffin, Ohio.

Turrets near completion. The Joint Systems Manufacturing Center (US Army Tank Plant) which is the only heavy armored tank factory in the United States. They build and refurbish Abrams tanks, Stryker armored personnel carriers, and other weapons systems.

Turrets near completion. The Joint Systems Manufacturing Center (US Army Tank Plant) which is the only heavy armored tank factory in the United States. They build and refurbish Abrams tanks, Stryker armored personnel carriers, and other weapons systems.

Main hull assembly line. Each station of the assembly is a full day of work before it moves down to the next station.

Main hull assembly line. Each station of the assembly is a full day of work before it moves down to the next station.

Side armor panel of a Stryker armored personnel carrier.

Side armor panel of a Stryker armored personnel carrier.

Workers use tricycles to move around the large plant.

Workers use tricycles to move around the large plant.

Heavy lubrication and rolling machinery, at the tank factory.

Heavy lubrication and rolling machinery, at the tank factory.

XM-1 Abrams tank prototype from 1979 preserved at the gates of the Joint Systems Manufacturing Center (US Army Tank Plant.)

XM-1 Abrams tank prototype from 1979 preserved at the gates of the Joint Systems Manufacturing Center (US Army Tank Plant.)

A man dressed as the Statue of Liberty hands out leaflets for an income tax preparation service, Tiffin, Ohio.

A man dressed as the Statue of Liberty hands out leaflets for an income tax preparation service, Tiffin, Ohio.

The Lima Bride wedding fashion show and vendor expo at the Veterans Memorial Civic Center in downtown Lima. The expo is sponsored by the local newspaper, The Lima News, and according to their count, 1500 people attended including 400 prospective brides.

The Lima Bride wedding fashion show and vendor expo at the Veterans Memorial Civic Center in downtown Lima. The expo is sponsored by the local newspaper, The Lima News, and according to their count, 1500 people attended including 400 prospective brides.

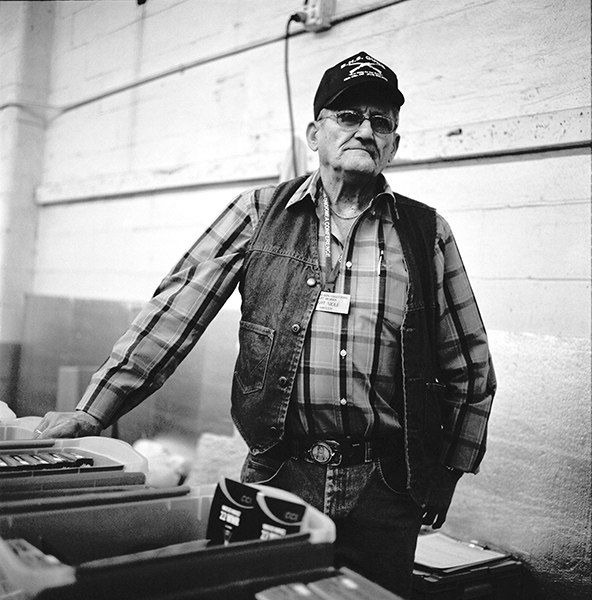

Gun show at the Allen County Fairgrounds. There were 450 tables with vendors selling hunting equipment, guns, knives, archery gear, and other sporting goods.

Gun show at the Allen County Fairgrounds. There were 450 tables with vendors selling hunting equipment, guns, knives, archery gear, and other sporting goods.

Wanted posters taped on the window of the Allen County Sheriff’s Office, a storefront in downtown Lima. It is not stated on each notice what each person is wanted for, but requests that the Allen County Probation Department be notified.

Wanted posters taped on the window of the Allen County Sheriff’s Office, a storefront in downtown Lima. It is not stated on each notice what each person is wanted for, but requests that the Allen County Probation Department be notified.

Mother with her child at the laundromat, out of downtown in a strip mall close to the interstate highway.

Mother with her child at the laundromat, out of downtown in a strip mall close to the interstate highway.

This couple on the right works in a video store, which they say has weathered the decline in video rentals that has shuttered larger businesses nationwide such as Blockbuster.

This couple on the right works in a video store, which they say has weathered the decline in video rentals that has shuttered larger businesses nationwide such as Blockbuster.

Girls and young women in a storefront dance and aerobics studio, Ada, Ohio.

Girls and young women in a storefront dance and aerobics studio. Ada, Ohio.

In addition to the tank factory, Lima has a large industrial base for a community of 40,000: an oil refinery, a Ford engine plant, a Proctor+Gamble factory manufacturing laundry detergent, and a large regional hospital.

In addition to the tank factory, Lima has a large industrial base for a community of 40,000: an oil refinery, a Ford engine plant, a Proctor+Gamble factory manufacturing laundry detergent, and a large regional hospital.

April 12, 2012

HEAVY METAL: AMERICA’S TANK FACTORY

Lima, Ohio looks like many mid-western towns. Downtown combines a few handsome government and office buildings with ubiquitous Rust Belt remnants of boarded up storefronts. There are traces of a bygone time when small town life was more intimate – an Art Deco Kewpee’s restaurant, the Depression-era Post Office — before businesses spread out to suburban strip malls. Pop. 38,000, midway between Toledo and Dayton in western Ohio, Lima is home to a large hospital, a Ford engine plant, an oil refinery, and the last and only factory manufacturing and refurbishing the heavily armored Abrams main battle tank.

An Abrams tank mounts an enormous 120mm cannon and several machine-guns. It thunders forward at 35 miles an hour, weighs 60 tons. Its crew of four live inside, protected by its armor and state-of-the-art night vision. A prime instrument of victory during the First Gulf War, it destroyed hundreds of Soviet-built Iraqi tanks with few losses and only one soldier killed. It can shoot farther with more accuracy and power. In the recent, much longer Iraq War, insurgents learned to damage more than 80 of them with roadside bombs and rocket-propelled grenades over the years, but even so, casualties were low.

The mainstay of both the Army and Marines, ten thousand were built over the last three decades. After Iraq and Afghanistan, it was seen in large numbers last year on the streets of Cairo during the Egyptian Revolution. Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait are all operators, as are Greece and Australia. The tanks are no longer made from scratch, but returned by train to Lima periodically for complete overhaul after getting stripped down in Anniston, Alabama. They come in affectionately as “rusties”, and drive out the door with everything new and improved except for the recycled armored hulls and turrets.

But with the American military relying more on special forces, drones and other hi-tech weapons, the future of the government owned, General Dynamics operated Joint Services Manufacturing Center (formerly the Lima Army Tank Plant) is very much in doubt. Overseas sales comprise up to a third of the plant’s orders, essential to its viability. This reflects both US foreign policy in the Middle East extending assistance to allies, and how funding that aid returns to critically support American industries.

President Bush and his Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld controversially reduced the size of the Iraq invasion force in 2003. Though candidate Barack Obama repudiated the war and its tactics that under-emphasized traditional, big-footprint operations, President Obama has inevitably continued the Pentagon’s shift of emphasis away from conventional Cold War doctrine to the realities of counter-insurgency. The military’s need for heavy weapons will not disappear, but it’s ever shrinking.

THE FACTORY

Created during the Second World War by the US Army, the plant is a sprawling industrial campus with 47 buildings on 370 acres, connected to two railroads. The main building is almost a million square feet, so workers ride tricycles to navigate around. From a wartime peak of 5000 workers including many women “Rosie the Riveters” in the 1940s, configuration to manufacture the Abrams tank began in 1978. There are currently over 900 employees, only ten percent of whom are women, and dozens of active-duty military staff.

With the Iraq War over for direct American combat and the Afghan War winding down, the government proposed mothballing and closing the plant until 2018, when the next cycle of refurbishment is due. That set off alarms throughout the community, uniting local politicians, management, and union workers to form Task Force Lima in the effort to save it. For the moment, building Stryker armored personnel carriers for the US Army and a large Abrams contract from Saudi Arabia keep the assembly lines humming. But plans for the new Marine Corps Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle (EFV) were cancelled.

At a meeting of the Task Force in January, Plant Manager Keith Deters spoke about competing to build an Israeli armored vehicle, the Namer. Mayor David Berger said, “Both tax cuts and revenue are needed” to sustain the military budget. Congressman Jim Jordan was ambivalent, remarking, “It’s a fiscal mess. I don’t think you’re going to see a whole lot done this year. It’s a growth problem; we don’t have the kind of growth we need.” All were committed to distributing a promotional video touting the plant’s capabilities, lobbying in Washington, and inviting dignitaries including Defense Secretary Leon Panetta to visit.

Speaking at greater length in March, Deters said, “The Army wants to use the Abrams until 2050. We rebuild it into a completely different tank: better electronics, better survivability. Completing a contract, it’s a ‘zero mile tank’. There were lots of Abrams tanks in Iraq. A battalion would come back and need upgrading. In 2007 we were completing 2.5 tanks a day. Right now we’re at one a day, going down to .65, and anything below half would be a problem. Significant layoffs are coming: over 200 people with an average of 15 years of service. We don’t know if there’ll be another contract at the end of the year.”

Deters is an engineer with more than 25 years at the plant, almost from the beginning of the Abrams program. As the Plant Manager he’s very proud of his facility. During a tour, he highlighted the advanced welding skills, the computerized precision machinery, and the freshly painted, completed tanks parked in neat rows outside.

THE WORKERS

The United Auto Workers (UAW) union hall is nestled next to Interstate 75 across town. Built of utilitarian concrete and spacious, the hall is rented out for disparate events like wrestling matches and weddings as well as union business. Both labor leaders and rank-and-file workers echoed the sentiments of their local elected officials and management.

Craig Kiefer, a quality engineer with 30 years at the plant and an officer of UAW Local 2147, spoke about the continuity of handing skills down. “I learned from the World War Two group – it was a sweet spot of history – former tank drivers. I was the youngest of that old core. But I worry that when my generation retires, how do we preserve that knowledge? There are standing threats, so we have to produce things instantly. If you scatter everybody, you can’t start again in two weeks. If they close this plant, they close down tank production in the United States.”

Kiefer related an all-too-common narrative of how the union has given up health care coverage, accepted reduced pay for new hires and the end of guaranteed pensions. He continued, “We’re in a new world, but still need to work with dignity and share profits. We have a teaming arrangement with management; it’s friendly. So we understand we need to be more efficient and embrace new technology even when it replaces people. But there is the constant anxiety of losing your job; reading about your job in the newspaper. Lots of other jobs are automated, high production. Here we preserve manufacturing capability. We know that what we do makes a difference. We have pride.”

Paul Matson, a highly skilled welder also with three decades of experience, agreed. “Whoever rides in that vehicle, their lives are in your hands. We get pictures of people that walked away after getting hit. ” His son Joel was also a welder at the plant but laid-off in November. Matson said, “If the phone would ring, he’d be back today.”

Ironically, the high tempo imposed by the last decade of wars was not entirely positive, Kiefer added: “It’s a double edged sword. We gained and added work supporting the war fighters, but every budget is only so big. When we fight a war, we can’t put the resources into design for new procurement.” So focusing on operational needs threatened the long-term research and development that would be more stable for the plant’s role in the permanent military-industrial complex.

That labor in the defense industry would be proud is not surprising, even as they’re uncertain about job security and eroding benefits. Over fifty percent of the workers are veterans. Gregory Gebolys, electrical troubleshooter and in charge of the union’s Veterans Committee, helped organize the construction of a war memorial outside the plant after 9/11, in the shape of an American flag. He said, “People are very patriotic here. We make a good wage. So UAW built the monument, and then gave it to the park system. It’s the tallest stationary flag in the country.”

When asked about the morality of their mission making war machines, the workers expressed their faith in the nation’s leaders and of massive strength. They accept that they implement decisions they don’t directly shape, and could recall only one colleague, years ago, who reassessed the consequences of his profession and quit to seek another career.

THE TOWN

Outside the factory gates and the union hall, it would be easy to forget or overlook the fact that such an important strategic installation is based in Lima. Rhythms of life follow patterns overflowing the rest of the country. Neighborhoods are ethnically clustered, if not actually segregated; a quarter of the people are African-American. One fifth of the town lives below the poverty line, and the population has fallen 40% over the last generation. Crime is proportionally high as a result.

Representative Jordan is one of the most conservative Republicans in Congress, trying to shut down mortgage relief programs designed to help homeowners suffering from the housing crisis. Mayor Berger, a Democrat, advocates for community block grants — federal assistance for affordable housing and infrastructure. He also supports same-sex marriage, collective bargaining rights for labor, and high-speed rail.

On a typical weekend in January, 400 women about to get married went to the Lima Bride fashion show and wedding cornucopia at the downtown Veterans Memorial Convention Center. Sponsored by the local newspaper, The Lima News, caterers, dressmakers, photographers, venues, and limousine companies rented booths and hawked their services. Marriage seems to be a recession proof industry.

At the Allen County Fairgrounds a few miles away, a parallel male universe of a gun show was happening at the same time. Terry Morgan, the president of the Tri-State Gun Collectors, said, “Guns sales are up 30% over the last two years, with an exploding increase in applications for concealed-carry permits. There’s fear of the government.” Morgan supports “castle laws” which give wide latitude to the use of deadly force in the home without any need to retreat even when safe.

The streets are mostly empty, bereft of pedestrians. The largest supermarket and retail outlet is the Wal-Mart far from the old city. Some distinct institutions remain, notably the historic Kewpee hamburger chain that still has five restaurants, from a peak of hundreds, and the Allen County Museum and Historical Society.

Art Orchard, the 83-year old guide there, paused before the exhibit commemorating the Second World War. Part of it was devoted to Medal of Honor winner William Metzger, preserving his uniform and other mementos. Orchard remembered, “he was a few years ahead of me in my high school. His plane was hit and on fire over Germany. He saved the crew and tried to pilot the plane down. Yes…the award was posthumous.”

In a silent museum with only a few visitors, Orchard spoke quietly. Just too young for the war himself, he never left his hometown of Lima and spent his working life in the heating and air-conditioning business. The Second World War birthed the tank plant, and on the other side of a century, tanks continue to roll off the production line.

Lima and its Joint Systems Manufacturing Center struggle to survive in a time of economic austerity, increasing class division, and political partisanship. The Abrams tank is as successful as the B-52 bomber in its longevity and utility. The workers who build it are skilled and loyal. The open questions are larger, on the changing nature of contemporary war with “asymmetrical” opponents, and the proper place of the military in a democracy as the appetite for intervention has fallen. There were no answers for those debates in Lima, only trepidations for the future.

*****

PHOTOGRAPHS + TEXT by Alan Chin / facingchange.org

With support from the Open Society Foundations