Kali and Paisley Watkins at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

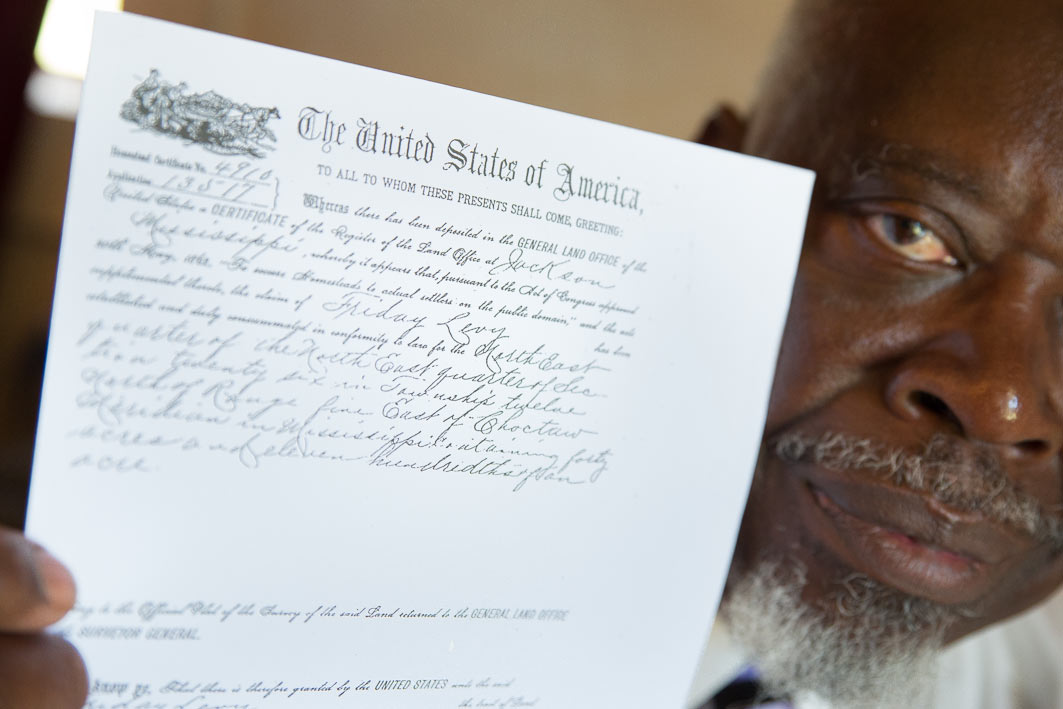

In the small town of Pickens, in the center of the state of Mississippi, William Primer pulled out a copy of the papers his fourth great-grandfather signed for 40 acres of land during Reconstruction. Primer has traced his roots back to slaves during the Revolutionary War, after much research at the Library of Congress and the State Archives of Mississippi. Later, we drove deep into the forests to a small, secluded church, half an hour from his home, to attend Sunday services where his fourth great-grandmother was laid into the cemetery. She was born a slave, as was her husband.

William Primer shows a copy of papers his fourth great-grandfather, Friday Levy, signed for the 40 acres of land.

Primer, a former Marine who later got a job raising the Mississippi state flag every morning at the State Capitol building in Jackson, says of the flag, “It’s not for me, not for my children.”

The inscription for Primer’s 4th great-grandmother reads in part: “Jane Levy, a slave, wife, and mother, came to the Madison County area with her slave master from North Carolina. She continued to endure the hardship of slavery and lived many years after slavery was abolished, serving as a midwife and paving the way for generations to come.”

It feels like the Civil War still burns slowly beneath the surface in places here and across the country, in the wake of the Charleston church massacre and the controversy surrounding the Confederate flag.

I had a unique opportunity to see this up close during a whirlwind, four-day, thousand-mile trip following the footsteps of The Washington Post’s Neely Tucker. My first day started early in the morning at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, where it was hot and humid, like standing in an all-day sauna with the blazing July sun beating down.

Mississippi House Speaker Philip Gunn speaks as protesters hold up signs calling for his removal because he supported changing the Mississippi flag.

The Neshoba County Fair is known for what’s called “Political Speaking” on Founders Square. Ronald Reagan debuted his general election campaign here in 1980 and with statewide elections coming up the following week here, candidates for office from the Public Service Commission to Governor had slots beginning just after 8 in the morning. Nearly a hundred people were already seated, and the Square filled up to standing-room-only as the day progressed. The Mississippi flag — which is the last state flag to incorporate the Confederate battle flag within its design — was a hot-button item on the agenda. Supporters handed it out along with placards. As Neely Tucker pointed out in his story, the common sentiment in white Mississippi is “that the Confederate battle flag is a historic banner that embodies the noble service and sacrifice of men who fought for ‘states’ rights.”

Mayor Bill Luckett of Clarksdale, below the flag pole next to City Hall without the Mississippi State Flag, after he decided to take it down. Clarksdale is 71 percent African-American. Several other towns have since followed suit, amid much controversy.

The next morning, I headed north to Clarksdale in the heart of the Delta. Mayor Bill Luckett, who owns a blues club with actor Morgan Freeman, took down the State flag flying over City Hall. He said, “It’s a sign of divisiveness and a sign of oppression and injustice and some go so far as to call it racist.” That night I visited Red’s Lounge where 83-year-old Leo Bud Welch sang the blues. Inside were tourists from as far away as France.

On my third morning I arrived in Oxford, Mississippi, where Robert Khayat, the former Chancellor of “Ole Miss,” the University of Mississippi, gave me a tour of the campus. His body is riddled with injuries from his days as an All-American football player at Ole Miss and then as a Washington Redskin in the 1960s. He went on to Yale, became a lawyer, and then Chancellor. Facing declining enrollment and the perception of declining quality of education, he decided to make drastic changes. In 1997, he banned the Confederate flag during football games evoking up a wave of anger throughout the state. He joked about the death threats he received, but he helped propel the school academically upwards, and, today, the student body is more diverse now with half from out of state.

I finished in Jackson, nestled on the Mississippi River; where Union General Ulysses S. Grant split the Confederacy in half and effectively doomed the Southern cause.

Along the river is a rundown house that flew the Confederate flag with “The South Shall Rise Again” inscribed, the couple living there told me to come early the next morning. I did and knocked for a while until the father of one of them answered, “I’ll get them up.” I heard him knocking on a bedroom door and yelling, but there was no response. I stood outside waiting for twenty minutes, photographing the flag. Finally, the father came back out. “I can’t get them up.”

I went on to visit the Vicksburg National Military Park and later that evening headed home.

Please see more photographs and Neely Tucker’s story at The Washington Post

Book I’m currently reading on the South, the Slave Trade and the looming Civil War by Christopher Dickey that I highly recommend: Our Man in Charleston: Britain’s Secret Agent in the Civil War South